Wild Thoughts Part III - Why Wilderness?

Wild Thoughts is a three-part blog series on wilderness ethics and management written in anticipation of the 2020 Adirondack Wilderness Symposium. Organized in part by Adirondack Council, the Symposium (dates TBD) will be open to the public and will feature programming on such varied topics as the legal status of wilderness in New York State, wilderness management in the era of climate change, and the more intangible, philosophical character of wilderness. Similarly, each segment of this summer-long blog series will tackle a different, broad wilderness-related question. Together, the Symposium and this series will attempt to offer a comprehensive, 21st-century consideration of wilderness as a legal concept, an ecological condition, and a cultural phenomenon.

“I walk toward one of our ponds, but what signifies the beauty of nature when men are base? We walk to lakes to see our serenity reflected in them: when we are not serene, we go not to them. Who can be serene in a country where both the rulers and the ruled are without principle? The remembrance of my country spoils my walk.” - Thoreau, “Slavery in Massachusetts”

In the weeks that I have written this blog series, I have watched a human rights crisis unfold at the U.S.-Mexico border, seen reports of dozens of mass shootings, and experienced the warmest month on record. I have read that anti-LGBT hate crimes are increasing, that the federal protections for threatened and endangered species have been gutted, and that North Korea tested two ballistic missiles within six days. As I write this, the Amazon Rainforest is on fire for the 72,843rd time this year.

Stories like these can be either galvanizing or paralyzing. They can prompt action -- a donation to a non-profit, a call to a representative, a protest -- or they can negate it. Sometimes the more disturbing headlines run through my mind all day, and I feel compelled to drop what I’m doing and act. But, much of the time, I hardly react, and I continue pretending that the “World” of World News is somehow not the world in which I live. Desensitization is also a kind of paralysis.

In the moments when so many problems in the news pose material threats to human life, it feels as though something as intangible as “wilderness” can wait. Wilderness advocacy is often concerned with aesthetic characteristics of remote tracts of land; it does not seem to be about direct and immediate threats to life and human dignity. So why visit wilderness, why think or write about it, why defend it at all? Why wilderness?

Wilderness and a Livable World

When the Wilderness Act of 1964 was written, protecting wilderness meant safeguarding habitat, natural beauty, and wild character for present and future generations. In the 21st century, wilderness advocates still defend these things. However, wilderness advocacy in the era of climate change now stands for something else too: a livable world.

By definition, there is no wilderness left. There is no area on the planet that remains untouched by climate change, thus “untrammeled by man.” Humans have altered the planet so drastically that scientists have declared that we live in a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene. The melting of permafrost above the Arctic Circle, periods of extreme drought and devastating wildfires in California, deadly monsoon rains and flooding in South Asia, -- these events are separated spatially, but they are connected by anthropogenic climate change.

Protecting wilderness is no longer just about protecting the survival of individual species in specific areas -- it’s about the survival of life on the planet. According to an August 2019 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), deforestation is a major contributor to climate change and makes up the majority of the 13% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with land uses such as agriculture and forestry. As outlined in the report, preserving natural areas such as wetlands and forests is one of the best mechanisms we have to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

Wilderness cannot wait.

What’s Next?

To make sure that wilderness does not become a backburner issue, we have to embrace new ways of thinking about it and advocating for it.

Slow Violence and Threats to Wilderness

We have a warped sense of the urgency of wilderness issues. Because wilderness typically contains things that have existed forever (old-growth forests, glacial plains, fjords, and the like), we don’t think of threats to wilderness as having the same immediacy and urgency as say, swine flu. However, something like a tree-cutting also puts life at risk by releasing carbon and preventing future oxygen-production and carbon sequestration. Forests are also home to 70% of Earth’s plants and wildlife. Even small-scale tree cuttings add up: According to a 2015 article in Nature, 15 billion trees are felled each year (making up an area about the size of Panama), and almost half of all trees have been cut down since the dawn of human civilization.

Writer and ecocritic Rob Nixon uses the term “slow violence” to describe environmental destruction that is “bloodless,” occurring in “slow-motion.” In Nixon’s words, slow violence is that which “occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all.” Opening the National Arctic Wildlife refuge to oil exploration. Rolling back the Clean Air Act. Tree cutting and ATV destruction in areas of the Adirondack Forest Preserve. We must call these things what they are -- violence against communities and ecosystems the world over.

Disavowing Racism in Conservation

To ensure that planet Earth has a future, the environmental movement must reckon with its racist past. Although many of the most idolized American environmental leaders were abolitionists (Thoreau, Emerson, Whitman), they also held white supremacist beliefs. As scholar Jedediah Purdy observes in the New Yorker, Thoreau’s essay, “Walking,” contains one of his most famous mantras --“In wildness is the preservation of the world." In this essay, Thoreau also writes: “the farmer displaces the Indian even because he redeems the meadow, and so makes himself stronger and in some respects more natural.”

At the onset of the conservation movement, conservation efforts were frequently tied to xenophobic, anti-immigrant priorities. One of the most prominent conservationists of the 19th century, Madison Grant, has been called both “the greatest conservationist who ever lived” and the “nation’s most influential racist.”

Grant was one of the major forces behind the creation of Denali National Park and the Everglades National Park, as well as the co-founder of the National Parks Association, Save the Redwoods League, and the New York Zoological Society. He was also the author of The Passing of the Great Race, a eugenicist manifesto which Adolf Hitler called his “Bible.” In the book, Grant sourced environmental ills to non-Nordic immigrants, whom he claimed held less respect for America’s natural environment. This mythology is still invoked today: Memorably, Fox News host Tucker Carlson attributed (and possibly equated) littering to unlawful immigration to the United States: “I actually hate litter, which is one of the reasons I’m so against illegal immigration.”

As writer Susie Cagle puts it, for early conservationists, “national purity and natural purity were inextricably linked.” It is no coincidence that a new strain of “eco-nativism” is emerging among contemporary domestic terrorists. The perpetrator of the recent El Paso shooting, whic h claimed 22 lives, has been connected to a manifesto that contains several Grant-like sentiments, praising Dr. Suess’ The Lorax, lamenting plastic pollution and urban sprawl, and sourcing environmental degradation to growing immigrant populations. The document was titled “An Inconvenient Truth” in an apparent nod to Al Gore’s climate change documentary of the same name.

To serve everyone, the conservation movement must root out its racist history. Here in the Adirondacks, that means doing the following things:

1. Think critically about rhetoric

Words matter. That’s why it’s time to reconsider the way conservationists speak about invasive species. It is not by accident that the language we use to describe “alien species” mirrors rhetoric invoked to label “illegal aliens” (e.g. #KeepThemOut, #StoptheInvasion). Are there ways to talk about the very real environmental and economic harm these species cause without falling into anti-immigrant tropes? By the way, I pretty much failed at doing this in a recent blog post.

There is also a xenophobic undercurrent to the way we speak about overuse in the Adirondacks. Sometimes, in conversations about overuse, there’s a subtle tendency to pin the problem on “the new Adirondack tourist” AKA non-white tourists. Let’s strive for better.

2. Unite the movement

Through a long chain of transmission, the racist attitudes that characterized the early environmental movement produced a schism among environmentalists today. The modern environmental movement can roughly be broken up into two groups: conservation advocacy and environmental justice advocacy. Environmental justice largely focuses on equal protection from environmental and health hazards for those disportionately affected by environmental ills -- indigenous groups, minorities and the poor. To grossly essentialize the two movements, conservation is about protecting land and wildlife and environmental justice is about protecting people.

However, I believe that efforts to preserve wilderness cannot and should not be separated from efforts to create greenspace in inner cities. Efforts to protect the air and waters of the Adirondacks cannot and should not be separated from efforts to reduce smog-induced asthma in Los Angeles and provide drinkable water for residents of Flint, Michigan. The climate changes which set the stage for Syria’s refugee crisis are the same changes that are shrinking Adirondack snowpack. What I mean to say is that wilderness advocacy cannot be merely an aesthetic or aristocratic issue, distant from environmental problems that disproportionately threaten communities around the world.

Although Adirondack residents and tourists are mostly white, race is relevant here. We must work toward an Adirondack conservation movement in which conservation goals are not separable from environmental justice goals. To do this, conservation must confront its whiteness, disrupt inherited racist thought patterns, and expand the idea of who can be a conservationist. In this sense, partnerships with groups that protect people, like the Adirondack Diversity Initiative, are as essential as partnerships that protect the Forest Preserve.

We must see and understand wilderness from all vantage points, from the High Peaks and from the hamlet. Gary Randorf, the first staff member and first executive director of the Adirondack Council, said it best:

“We are and will continue to set an example of how to do it – that is saving a wilderness that includes people. If we fail, we fail not only our state, our country and ourselves, but also the world.”

Wild Hope

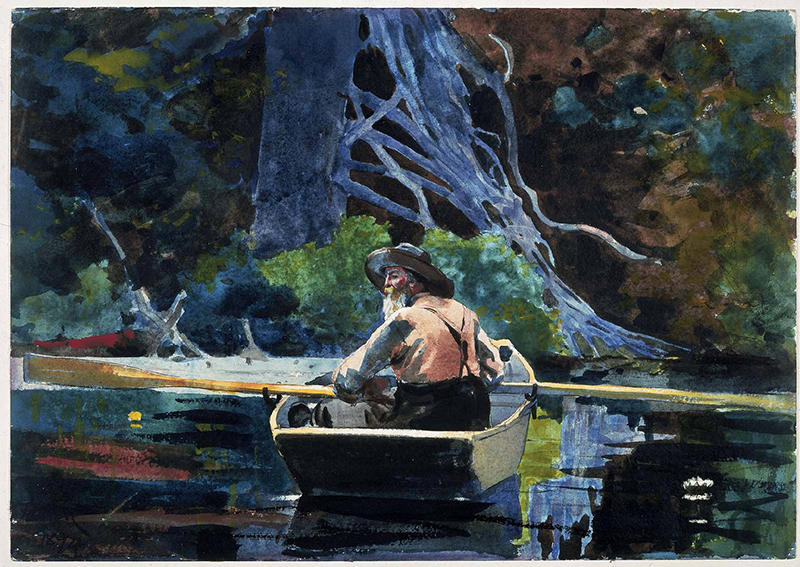

Wilderness is a place of extreme, absurd, stirring beauty. There is so much ugliness in the world that this fact has to count for something. When I am in a wild place, surrounded by sky-scraping pines, or enveloped in the rippling blue waters of a lake, I feel an overwhelming smallness. I feel a sense of great responsibility to simply let land be. This is my second, softer answer to the question, “why wilderness?”

I know that conservationists move mountains by simply preserving their existence.

Why wilderness? If you ask a dozen wilderness advocates this question, you’ll likely receive a dozen answers. What is yours?

Julia Randall is from Albany, NY and graduated from Williams College this year with a degree in English. As a Clarence Petty Conservation Intern, she works on a variety of projects related to overuse and wilderness management, including a white paper that envisions an EV shuttle system in the Adirondack Park. An aspiring environmental lawyer, Julia is passionate about climate justice and getting the words right. In her free time, she enjoys hiking, making music, and frequenting Donnelley’s Ice Cream.

Julia Randall is from Albany, NY and graduated from Williams College this year with a degree in English. As a Clarence Petty Conservation Intern, she works on a variety of projects related to overuse and wilderness management, including a white paper that envisions an EV shuttle system in the Adirondack Park. An aspiring environmental lawyer, Julia is passionate about climate justice and getting the words right. In her free time, she enjoys hiking, making music, and frequenting Donnelley’s Ice Cream.