What We Do

The Adirondack Park is renowned for its vast wilderness areas, expansive forests, pristine rivers and lakes, breathtaking mountain summits, and world-class outdoor recreation areas. The Adirondack Park is unique in part because it doesn’t have an entrance gate or a centralized access point. Among the state-protected wildlands, a patchwork of private lands and communities exists, where 130,000 permanent and 200,000 seasonal residents reside, and 12.4 million annual visitors visit each year.

Increasingly, people are seeking opportunities to spend time in nature, engaging in activities such as hiking, camping, or paddling. With the rise in visitors, the wildlands of the Adirondack Park require more resources, planning, and staffing to be better protected as a world-class outdoor recreation destination, for us and our future generations.

Unaddressed overuse in certain locations within the Adirondack Park is putting pressure on natural resources and, in some cases, creating unsafe settings for visitors, thereby harming the quality of the wilderness experience that is central to the Adirondack Park’s legacy.

What is Overuse?

Overuse occurs when the volume and wear from use cause a location to sustain damage to natural resources, and/or negatively impact the user’s experience or management objectives for that area.

Overuse in the Adirondack Park

More and more people are seeking to spend time recreating on our public lands, and this trend, coupled with major funding for tourism campaigns, has led to a huge surge in visitors to the Adirondack Park.

In 2017, 12.4 million people visited the Adirondacks. That’s almost 500,000 more people than in 2016. This has been reflected in the number of people visiting our wildlands. According to a regional tourism survey by the Regional Office of Sustainable Tourism (ROOST), 72 percent of day trippers come to the Adirondacks for a wide variety of outdoor activities. Of those people, 85 percent come for hiking, making it the most popular outdoor activity in the Adirondack Park. Most of these people are concentrated in key regions with accessible points to Wilderness areas and nearby amenities, such as the Old Forge, Lake George, Lake Placid, and Keene communities. So much so that the Eastern High Peaks Wilderness Area near Lake Placid has been designated as a Leave No Trace Hot Spot for 2019.

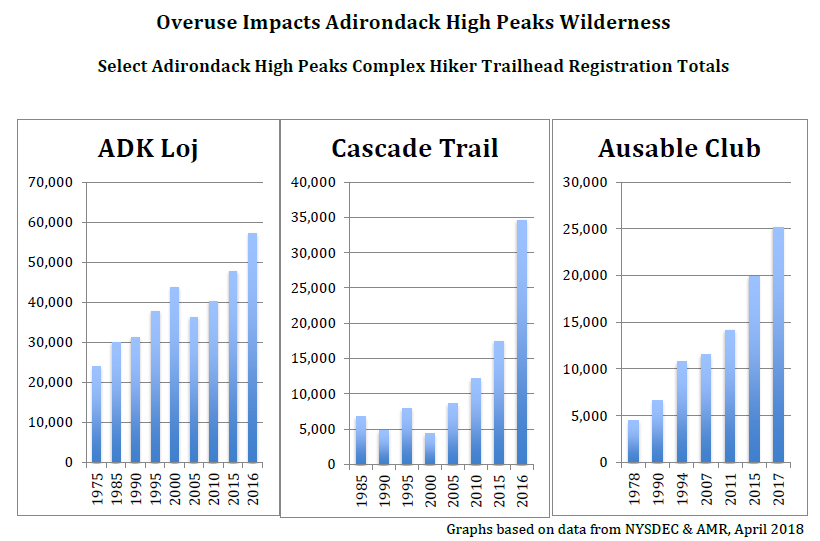

As shown in the chart below, there has been a surge in hikers at popular Adirondack trailheads in the Lake Placid region. Since 2005, the number of hikers registering at the Cascade Mountain trailhead has more than tripled. Last year, this trailhead was temporarily relocated. A new, sustainably designed trail is being built to meet site specifications and intended use. However, implementing new trail designs requires more resources, trail crews and time. And all trails, even well-built trails, degrade over time without a level of maintenance that is currently lacking.

Effects of Overuse:

1. Trail Damage & Erosion

Without updated trail design and robust annual maintenance, overuse can cause soil loss, erosion, loss of vegetation and negative impact to wildlife such as martins or bobcats. In 2018, an analysis by Adirondack Park trail professionals found that over 130 miles of trails in the High Peaks need significant redesign and annual maintenance to ensure the integrity of the resource. Many Adirondack trails have been improved through drainage, trail hardening, relocations, and hiker education. However, trails that see increased use, but have not been redesigned or hardened, and maintained, are getting worse.

Trails that are improved and redesigned but not maintained see significant damage and erosion. Some trails in the High Peaks region are now as wide or wider than a road. There are places with more than 2 ½ feet of soil loss due to increased hiker traffic, with no erosion prevention controls in place or being regularly maintained.

Key trail issues:

Erosion occurs when the volume of wear from use exceeds the trail’s capacity and damages it. Eroding soil degrades nearby water quality by increasing turbidity, or the sediment load in waters, and impacts wildlife, plant life, and the structure of a waterbody.

Widening occurs on trails where users trample vegetation on the sides of a trail and cause the designated trail to get wider and wider. Some Adirondack trails have tripled in width to over 25 feet in less than 30 years. Widening usually occurs when users try to avoid a muddy spot or obstacles like rocks, trees, or stumps. This can also lead to the development of trail diversions, where another “trail” is created by people stepping off the original trail to circumvent obstacles.

Fortunately, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), third-party professional trail crews, and volunteer organizations like the Adirondack Mountain Club, the Student Conservation Association, the 46ers, the Bark Eater Trails Alliance, and others know how to utilize sustainable trail design and perform adequate reconstruction and maintenance to prevent erosion, if provided with the resources needed. Without the work of these and other organizations, high use will continue to cause soil loss, compaction, erosion and damage to the Adirondack Wilderness and other areas. Read press release: “Pre-Study Finds Need for Trail Redesign and Repair”

2. Damage to Vegetation

While the Adirondacks are home to some of the most spectacular views in the northeast, they are also the natural habitat for rare, threatened and endangered species, including fragile alpine plants. Currently, there are 27 alpine plant species in the High Peaks.

The increase in the number of hikers taking advantage of New York State’s beautiful summit views has created another obstacle for alpine vegetation. With overcrowded summits, hikers will often trample these fragile alpine plant species in search of a view, unknowingly putting these organisms at risk of extinction. The combination of a short growing season, acidic soil, frigid winters, and brutal wind makes it extremely difficult for plants, such as Boott’s Rattlesnake Root, Dwarf Willow and Alpine Azalea, to survive.

Trail widening, soil compaction, and erosion remove the small areas of open canopy where rare, threatened, and endangered plants, such as the pink lady’s slipper, trillium, and ferns, can be found.

To minimize the effects of overuse on these plants, hikers should stay on rocks and trails and practice Leave No Trace Outdoor Skills and Ethics.

Efforts by organizations like the Adirondack Mountain Club to educate hikers have helped prevent damage to alpine vegetation in the face of growing numbers of hikers since the 1960s.

3. Clean Water Polluted

As the number of visitors to our wildlands increases, there is a growing concern about the impact of improper waste disposal. The Ausable River Association completed a study examining the correlation between fecal indicator bacteria and an increase in visitors to the High Peaks Wilderness Area. They specifically examined the start of the Ausable River watershed, which begins in the High Peaks Wilderness, a highly utilized area. The study looked for E. coli bacteria (Escherichia coli), because it is an Environmental Protection Agency recognized indicator of fecal contamination of drinking and recreational water. Water with high levels of E. coli can pose health risks to people who recreate in or drink from the water. These bacteria typically enter backcountry water bodies through human excrement. They can also be distributed by rainwater runoff, animal carcasses, malfunctioning wastewater treatment plants, and leaking septic systems.

The study was conducted at 10 sites, which span a spectrum of high to low overuse. After testing, the Ausable River Association found human fecal contamination in the water of the High Peaks. At all testing sites, water was found to be unsafe to drink without proper treatment. Furthermore, there were higher concentrations of E. coli near higher use areas. This creates potentially hazardous conditions for visitors who may be unfamiliar with treating water or lack access to the necessary equipment.

A comprehensive solution is needed to address this issue. Educational outreach programs about proper human waste disposal are critical in not only this area but countless others. Also, infrastructure such as privies and port-a-johns at trailheads, as well as additional privies along trails, would significantly reduce this water contamination issue.

4. Wildlife Impacts

With 12.4 million people visiting the Adirondacks each year, there is a growing impact on wildlife. In 2017, there were 143 bear complaints and five bears euthanized in the Park. In 2018, in the same region, there were 503 complaints and 15 bears euthanized. Much of the increase in problem bear activity was the result of a dry spring, but was further complicated by the increased food availability from improper storage by campers and hikers. The growing food source is a result of more human activity in the backcountry, especially in popular crowded campsites known for bear activity, where the animals become habituated to human interaction.

Loons are another species that can be negatively impacted by human disturbance. Although they are resilient animals, loons have a breaking point that can lead to loon deaths or nest failures. People are often fascinated by loons and want to paddle or boat closer for a better look, but approaching a loon too closely can cause them to abandon their nests and eggs. If loons leave their nests for a long time, the eggs will not be incubated and fail to hatch. Also, the wake from a motorboat or jet ski can destroy a loon nest and harm the chicks in it.

As more people spend time on Adirondack water bodies, it is crucial to recognize that our fascination with loons can be detrimental to their populations if not properly managed. Observing loons from at least 150 feet away with binoculars will ensure that the birds are not overly stressed and that the nest will not be compromised. People driving motorboats or jet skis should stay away from the shoreline and keep a constant eye out for adult loons, chicks and their nests.

5. Hiker Safety

Since the 1970s, the Adirondack Forest Preserve has expanded from approximately 2.2 million acres to over 2.6 million acres, resulting in an increase in the amount of public land per Forest Ranger from 28,516 acres to 53,752 acres. At the same time, the responsibilities and priorities of the Forest Rangers have changed, and their time spent patrolling in the backcountry has decreased significantly. Concurrently, the number of people who choose to recreate in the Adirondacks has also grown. With that comes the increased likelihood that someone will get lost or hurt.

Additionally, a greater demand is placed on implementing additional safety measures, whether that involves improving personal safety or ensuring proper external measures are in place. Today, Rangers respond to an average of 350 incidents per year; almost one per day. By comparison, in 1970, Rangers responded to 143 search and rescue incidents per year. With 12.4 million people visiting the Park each year, Forest Rangers and other staff who help them are working beyond their capacity. This puts the resource, visitors, and the Rangers themselves in jeopardy.

6. Sense of Solitude Lost

The large crowds in the Adirondack Park directly correlate with people’s increased interest in attaining a positive outdoor experience. Maintaining this sense of place and solitude in the Adirondacks plays a huge role in preserving the Park as a world-class outdoor recreation destination. Unfortunately, the impacts of overuse, such as trail widening, overcrowded parking lots, the number of people on trails or summits, trampled vegetation, and visible human waste and trash, have a detrimental effect on that experience.

In 2018, the Adirondack Council conducted a survey to determine which impacts of overuse most negatively affected hikers’ sense of solitude. The survey results showed the signs of overuse that most impeded hikers’ enjoyment were visible trash (25%), visible human waste (22%), trampled vegetation (16%), and crowded trails and summits (16%). See survey results

Below is a short time-lapse video showing over 500 hikers summiting Cascade Mountain in 2017, before the trail reroute, on a holiday weekend.

Managing Overuse

It is clear that overuse is a complex problem, and it is going to take a comprehensive approach to address it. It’s unfortunate, but we’re not alone. Overuse is occurring in other state, national and international parks across the world. A lot can be learned from other state, national and international governmental agencies and organizations on how they tackle overuse.

The framework that is most relevant to the Adirondacks right now is the agreed upon Six Best Management Practices for Wildlands Management. They’ve come about from Dr. Chad Dawson, John C. Hendee and their book, “Wilderness Management: Stewardship and Protection of Resources and Values.”

This comprehensive framework is essential for preserving the natural resources of the Adirondacks, ensuring safe and enjoyable user experiences, and preserving the wild character of the Park while upholding management objectives.

The Six Best Practices for Wildlands Management

- Comprehensive planning for Forest Preserve protections with all agencies and jurisdictions. Given the interconnected nature of the Adirondack Park, we must look at natural resource protection, visitor use experience, wild character, human health, and safety in a holistic and comprehensive manner.

- Expanded Outreach and Education for visitors and residents, including backcountry safety and accident prevention. This allows users to make decisions that minimize their impact on natural resources, foster a positive wilderness experience, and stay safe. Education can help users stop avoidable impacts, minimize unavoidable impacts, and preserve the quality of the wilderness experience.

- Front-Country Infrastructure including roadside safety, visitor information, and orientation services, personnel, restrooms, parking lots, parking enforcement, boat inspection and decontamination stations and launches, intensive use options (on lands so classified) and lodging (on private land). Without these services and facilities, we create a situation that puts more stress on the backcountry infrastructure and decreases hikers’ safety.

- Back-Country Infrastructure that does not impinge on the protection of natural resources and wild character, including trails, camp-sites, lean-tos, privies, necessary bridges and personnel. Without the various infrastructure in place, trails and campsites can’t support current use without hurting natural resources. Infrastructure should preserve or restore the area’s wild character.

- Limits on Use at various times and locations when education, outreach, and infrastructure management fail to address carrying capacity. When this happens, it is important to utilize various forms of limits, such as permits or fees. Without them, there can be significant environmental damage due to overuse.

- Funding and Personnel, from the state and/or other partners, are needed for all state management agencies to ensure the long-term stewardship and preservation of Forest Preserve lands and waters within the Park. With the number of people hiking in the Adirondacks increasing, the need for more state employees, such as Forest Rangers and foresters, as well as non-state personnel, including Summit Stewards, is also growing. These personnel are crucial for monitoring limits, back-country infrastructure, and front-country infrastructure, as well as updating and creating educational resources. Without an adequate number of staff, they, too, like the trails, are over their carrying capacity.

By implementing a comprehensive plan that encompasses all Six Best Management Practices for Wildlands Management, we will have a brighter future for the next generation to enjoy and explore the Adirondack Park.

Our Reports & Work on Overuse

1.Study: Adirondack Hiking Trails Don’t Meet Design Standards

This report finds that more than half of the trail mileage in the Adirondack Park’s central High Peaks Wilderness Area is too steep to remain stable and fails to meet the modern design standards for sustainable trails. The survey found 167 miles of trails in the middle of the High Peaks Wilderness whose slopes exceed eight percent and are not sustainable unless hardened. Read more

2.Overuse Degrades Adirondack High Peaks Trails; Captured in Before & After Photos

During busy weekends in the High Peaks and at certain locations around the Park, there are numerous cases of unaddressed overuse. This threatens natural resources, creates an unsafe environment for people recreating, and weakens the wilderness experience for which people escape to the Adirondacks.

This trail analysis utilizes before-and-after pictures to emphasize the need for a redesigned and rebuilt trail system in the Adirondacks, ensuring the Park remains a world-class outdoor recreation destination. Read more

3. Survey Finds Adirondack Hikers Prioritize Protection of Wilderness over Recreation

The majority of hikers, by 70% to 20% believe the state should prioritize the protection of wilderness character and sense of solitude over expanding recreational opportunities.” This was one of the findings of an Adirondack Council survey conducted in the High Peaks region in 2018 that interviewed over 1,000 groups of hikers. The survey assessed hikers’ perceptions of overuse, their level of support for potential state land management strategies, and user characteristics (age, race, residence, and level of hiking experience). Read more

4. Study: 130 Miles of High Peaks Trails Need Major Work

During an assessment of Adirondack hiking trails, the Council found that over 130 miles of trails are heavily damaged. This is the result of overuse, poorly designed trails, or a lack of maintenance. With help from trail professionals such as the Adirondack Mountain Club, Adirondack 46ers, Hamlets to Huts, Adirondack Trail Improvement Society, and Splitrock Stonework, the Council was able to produce a map that shows trails in major need of redesign, reconstruction and repair. Read more

5. Study: Adirondack High Peaks Wilderness Visitors Exceeding Capacity

The Council’s 2017 High Peaks regional parking lot survey found that almost 80 percent of all trailheads at the entrance of the High Peaks were above their peak capacity during the weekends. In total, 35 parking lots that were originally built to handle 1,000 cars frequently had over 2,100 cars trying to park there. This overuse created unsafe conditions, harmed natural resources and degraded the wilderness. Read more See map