A Look at Regional Planning Beyond the Blue Line

August 26, 2019

By: Will Lutkewitte - Clarence Petty Vision Intern

I have had the pleasure of working as a Clarence Petty Intern for the Adirondack Council this summer assisting with the Council’s long-range VISION Project. The project creates a vision of the Adirondack Park’s future that inspires broad support, far-sighted policies, and specific actions that together deliver on the promise of the Park. It will make recommendations and advocate for transformational actions that promote resilient and economically vibrant human communities and protect the natural resources and wild character of the Adirondacks.

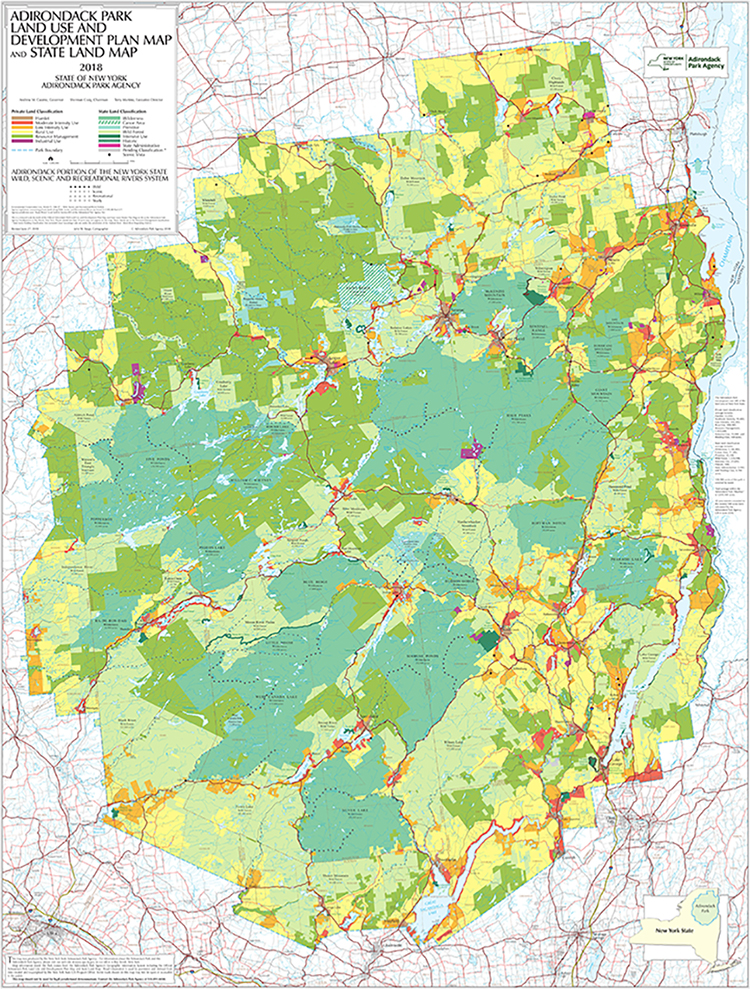

One facet of the project addresses Adirondack Park governance and ways it can be positioned for success in the future. The Adirondack Park Agency (APA) was formed 48 years ago, with forward-thinking ways to preserve and protect human interests, both environmental and developmental. The Adirondack Park State Land Master Plan (SLMP) and Private Land Use Development Plan (PLUDP) were adopted and have faced many challenges over the decades in their implementation “to protect the public and private natural resources of the Adirondack Park.”

Click on map to enlarge

Click on map to enlarge

The APA isn’t the only regional land planning agency in this country, let alone the only one that faces challenges with implementation of a complex mission. Since 1971, many other regional land planning agencies have been established with similar missions of preserving unique natural resources around the country and world. Some of these agencies face similar challenges to the APA and they provide examples of potential solutions. I have spent the summer looking into these other agencies and missions that could provide model solutions to challenges in Adirondacks.

The Research

From recommendations compiled during interviews conducted with land management professionals, I compiled a list for research of 11 places from across the country and world with similar agencies and missions. These places include:

- Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (NV & CA)

- The Pinelands Commission (NJ)

- Act 250 (VT)

- The Land Use Planning Commission (ME)

- The Columbia River Gorge Commission (OR & WA)

- The Palisades Interstate Park Commission (NY & NJ)

- The Cape Cod Commission (MA)

- The California Coastal Commission (CA)

- The South Carolina Coastal Council (SC)

- Abruzzo National Park (Italy)

- South Downs National Park (England)

I looked to cross-compare the Adirondacks with these other areas, hoping to find policies, programs, and ideas that could provide helpful insight for meaningful change in the Adirondacks. The information I have collected will assist with the recommendations made in the VISION project. Though this blog post is a reflection of what I have found interesting in my summer search, the data presented in this blog post is not an official recommendation of the VISION project.

I largely conducted my research through resources available to the public via the internet, using accessible websites for the planning agencies/commissions, state and national law libraries, local news outlets, and other sources. Realizing that making use of only the internet for research would restrict my understanding, I conducted phone interviews with more involved voices working in the regions I was investigating, largely local environmental non-profits and recommended contacts. The goal was to get a snapshot of what these regional governing bodies looked like, along with the challenges they face and how they have been addressing them.

The Findings

The common thread with all of the areas is a mission that seeks to balance preservation of environmental resources and the developmental interests of those that live in and around the region. The way each plan carries out that balance differs.

Appointment Structures

Each of these regional planning agencies has appointed membership positions to their decision-making board. The number of appointed positions vary from five to 27 members across all the regional planning boards. The positions and the ways people are appointed to those positions also varies.

Similar to the APA’s 11-member board, Vermont’s Act 250, which helps statewide with land planning, has a Natural Resources Board that has five appointment positions (with five alternate appointments for a total of 10 positions) all made by the governor. However, as with other regional bodies, the appointing power doesn’t solely belong to the governor.

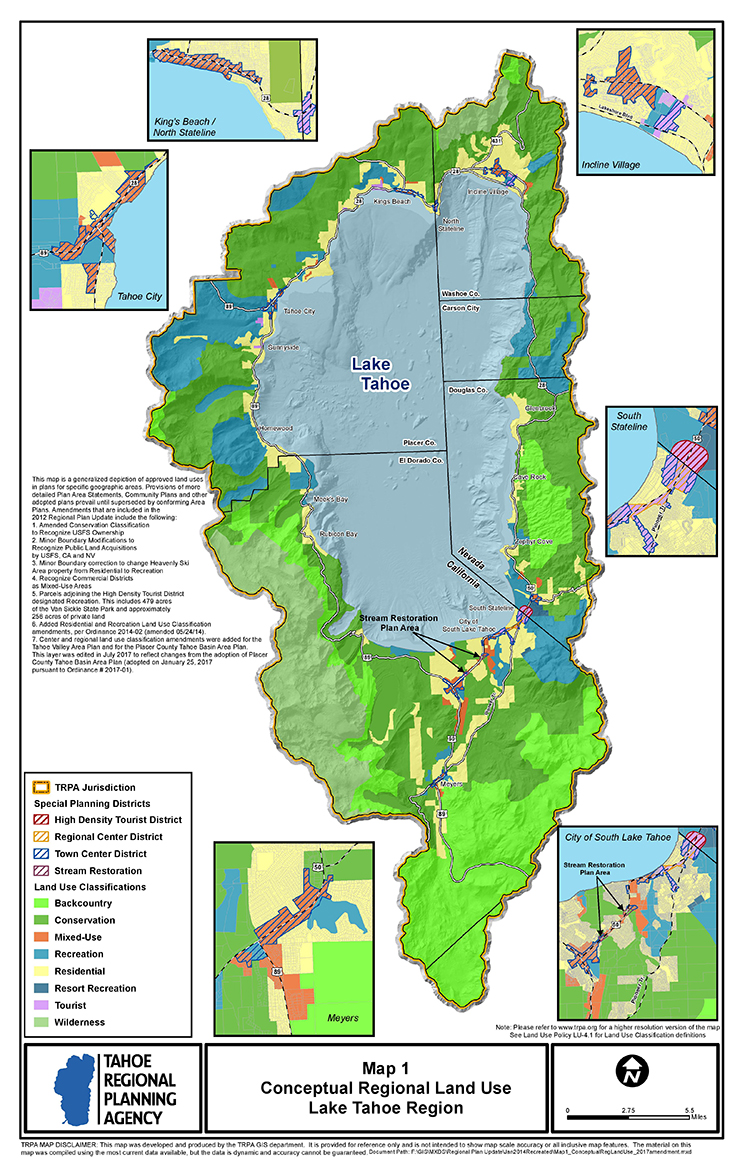

The area that stands out in appointment power is the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency (TRPA) in the Lake Tahoe regional watershed that borders Nevada and California. The TRPA has 15 members, which consists of seven members from California and seven members from Nevada. There is one appointment by the President of the United States to a non-voting role, due to the federal involvement in the Lake Tahoe watershed. Click on map to enlarge

Click on map to enlarge

Out of the 14 voting members, only three are gubernatorial appointments (two by the Governor of California and one by the Governor of Nevada). The rest are appointments by various officials in California and Nevada. Six are appointed by the local county boards or large city councils in both states; four are appointed by different state positions in both state governments (such as the speaker of the assembly of California or the Secretary of State for Nevada); one appointment is made by an agreement from the other six appointments of the Nevada delegation on the TRPA.

Qualifications

Another dimension of the appointment process for the decision-making positions on these agencies is the qualifications of the appointees. Similar to the APA, other agencies have an apportionment of members that must reside within the boundaries of the respective region, to represent the voice of the people that the land planning agency is impacting most. Beyond where they reside, the APA has a political affiliation requirement with a goal of keeping party affiliation and political perspective in balance. Other commissions take different measures for keeping a balance of perspectives on the appointed boards.

The Cape Cod Commission, in charge of land use planning for Cape Cod in Massachusetts, includes a diversity requirement where two appointees must be from an ethnic minority group, and one appointee must be Native American. The Maine Land Use Planning Commission, responsible for the planning of areas in Northern Maine, includes a requirement that the Governor’s appointment must have expertise “in commerce and industry, fisheries and wildlife, forestry or conservation issues as they relate to the commission's jurisdiction.”

Regional Planning

At the core of each planning agency is a regional plan that the agency sets out and looks to uphold. At their basic level, all of these plans look to protect an area. On the other hand, the differences are numerous. Some plans manage areas much smaller than the Adirondack Park, while others are similar in size. And a few plans require the shared cooperation of two states like the Columbia River Gorge Commission, which serves the Columbia River Gorge Scenic Area on the border of Oregon and Washington, and the Palisades Interstate Park Commission, which straddles the Palisades Park on the border of New Jersey and New York.

Land Use Designations

As these are regional plans from across the country, landscapes and uses vary greatly. Thus, as expected, land use classifications are quite different across regional plans, although there are also similarities across many of the plans. One such similarity is the effort to concentrate development into designated areas similar to hamlet areas in the Adirondacks’ PLUDP. In other plans these areas may be designated under titles such as villages, urban or organized areas.

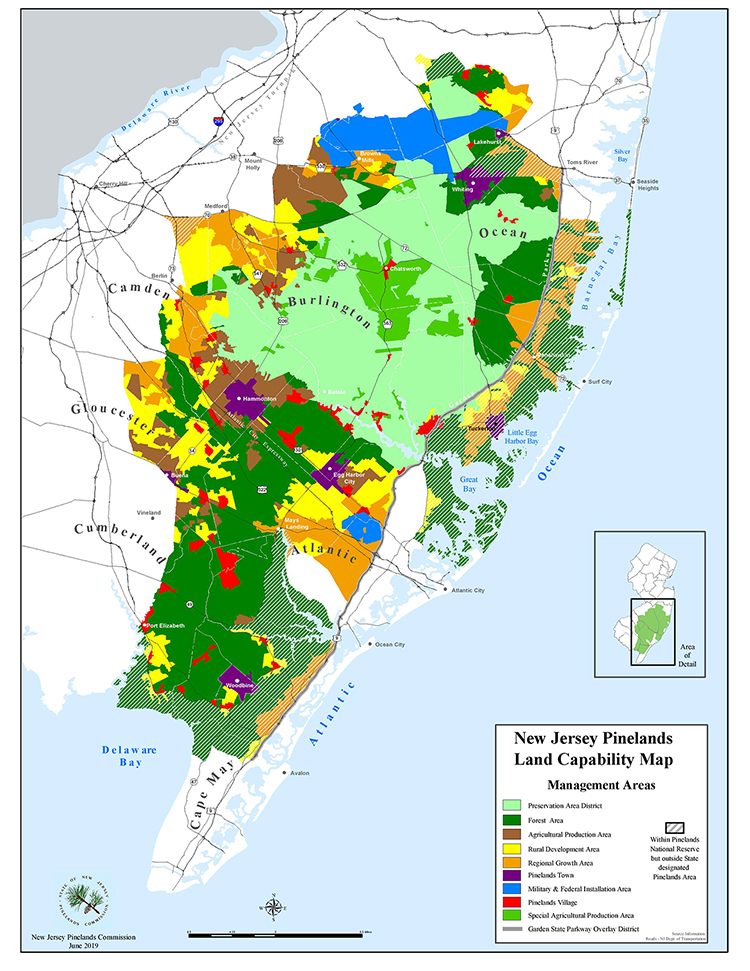

Designations for strongly protected environmental areas and intensely developed areas appear in every plan, but differences exist in the details of how these areas are protected or developed. One example is that in hamlet areas within the APA Act, the focus is on the concentration of development such as building and homes within them. In contrast, in the Comprehensive Management Plan of New Jersey’s Pinelands Commission, protecting the Pinelands of Southern New Jersey, there is an additional focus in the Pineland hamlet-like villages on the accessibility to public service infrastructure, such as sewers, in these developed areas.

Click on map to enlarge

Click on map to enlarge

There is at least one land use designation that shares an almost-verbatim definition in every United States regional area that I researched: wilderness. Despite the Adirondack Park SLMP’s definition of wilderness being a word or two different than areas protected under the National Wilderness Preservation System, established by the Federal Wilderness Act in 1964, there is a shared sentiment of intense protection. The policy difference mainly lies in how they are protected; one being secured by a state constitution clause, the other being protected by a federal act.

Local Land Use Plans

Approved municipality or town land plans by the respective regional planning agency were another difference among the land planning agencies. The APA does not require local municipalities to have an approved Local Land Use plan, though it still needs to fit the proper land use designation under the PLUDP. By stark contrast, the NJ Pinelands Commission requires all 53 municipalities within the regional boundary to have a plan approved by the Commission. On the opposite end of this question, the Columbia River Gorge Commission has virtually no jurisdictional authority over the planning and development within the urban areas inside the regional boundary. It is charged in its responsibilities with making minor adjustments, if needed, to the urban boundaries, but it only has authority over which activities (development, recreation, or the like) are and are not allowed outside of an urban area boundary.

Concluding Remarks

This project of comparing these land-planning agencies has been an opportunity to understand a variety of efforts that seek to balance the developmental and environmental interests of humanity. By looking at existing models, we can learn from other areas about planning, processes, or structures. We can learn what works and why without having to go through our own lengthy trial and error process that could take decades to get the same information. Of course, because an idea works in one region doesn’t necessarily mean it will work in another, but looking at other ideas in practice opens the door for concepts that could potentially prove helpful here in the Adirondacks.

Will Lutkewitte is a senior from Cornell University, studying Environmental and Sustainability Sciences with a concentration in policy and governance. Working as a Clarence Petty VISION Intern, he helps with gathering information and data for the VISION project, focusing largely on the research of agencies and plans in other regional areas similar to the Adirondacks. Beyond graduation, Will would like to work in policy, securing a brighter future for environmental resources. He spends his free time hiking the 46 High Peaks as an aspiring 46er and training as a thrower for the Cornell Track team.